Vaughn Stewart and Brad Haynes met when they were 10, as fourth graders in Anniston, Alabama. Despite differences in appearance and attitude, they forged a close friendship that would endure for more than two decades.

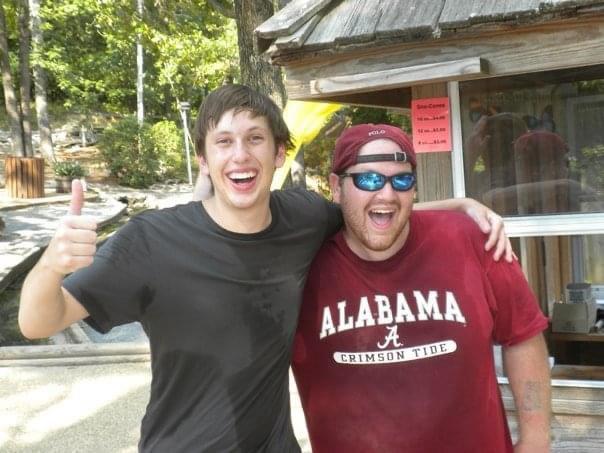

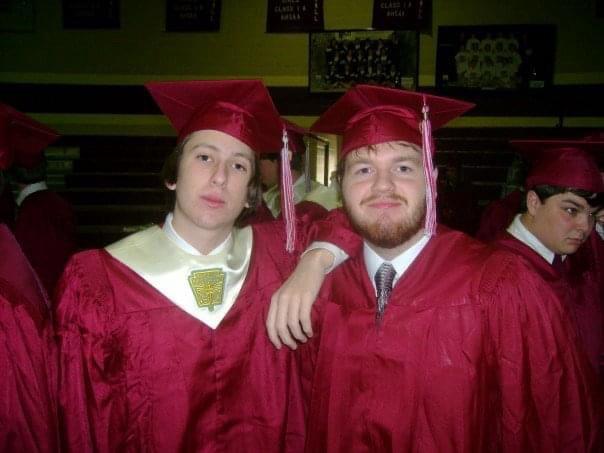

“He and I looked very different in the sense that he was kind of an early bloomer, and I was a late bloomer: I was tiny and baby-faced, and he was bearded and prematurely balding,” recounted Stewart, an adopted Marylander currently in his second term as a Montgomery County member of the Maryland General Assembly’s House of Delegates. And while the pair shared a similar sense of humor and an affinity for many of the same movies and TV shows, Haynes’ outlook on life complemented that of Stewart and other “Type A wannabe achievers” in their circle of friends.

“Brad kind of pushed us toward a carpe diem sense of life. He was always the person on a Friday or Saturday night who was like ‘Hey guys, we’re not going to be around forever, let’s go do this thing that might be slightly irresponsible instead’,” Stewart, now 35, chuckled. After their high school graduation, Stewart headed north to college and then law school in Pennsylvania and New York, while Haynes opted for the University of Alabama–but they talked by phone almost weekly and made periodic trips to visit each other.

And then, last October, Stewart received the worst imaginable news: Haynes, at 34, had died from a fentanyl overdose after years of an addiction that left even close friends like Stewart to guess as to when it started – and why. “It’s very, very devastating to have been best man at your best friend’s wedding within eight years of being a pallbearer at his funeral,” said Stewart, the emotion evident in his voice. “I still can’t believe it–it doesn’t feel very real.”

Stewart’s self-described Type A side soon kicked in, as he channeled “being in a state of shock and grief” into action “by diving head first into all these research papers about opioid use disorder.” The upshot was legislation introduced earlier this month, HB 1155 to compel hospital emergency room physicians to offer treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD) that have demonstrated an ability to reduce the potential for patient relapse – and death.

If passed, the bill – the subject of a hearing Friday afternoon before the House Health and Government Operations Committee – would make Maryland the second state in the nation, after Massachusetts, to put such a law on the books. It was crafted by Stewart in direct response to the circumstances surrounding the death of Haynes – who died from a second overdose within hours of being discharged from the emergency room of an Anniston-area hospital for treatment of an initial overdose.

This marks the first time that Stewart – a Democrat first elected in 2018 to represent Rockville/Silver Spring-based District 19 – has sponsored legislation related to opioid abuse. “Part of the story here is that I think it’s a shame that I haven’t been involved in this space before, and it’s a shame that it took a personal tragedy for me to get more involved in the issue because it is so important. But legislators in Annapolis tend to be very siloed in the issue jurisdictions that dominate their respective committees,” added Stewart, who serves on the House Environment and Transportation Committee.

To pick up support for his proposal, Stewart reached out to a relatively new friend – marking another instance of Stewart forging a connection with someone in many ways his opposite.

Mike McKay – who overlapped with Stewart for a term in the House before being elected to the Maryland Senate in 2022 – is a member of the General Assembly’s increasingly conservative Republican minority, just as Stewart is firmly in the progressive camp of a Democratic majority that has moved decidedly left in recent years. But, as they often stayed overnight in Annapolis during the legislature’s 90-day annual sessions, Stewart and McKay struck up conversations – and ultimately a friendship – in the lounge of the Marriott Waterfront Hotel.

It was geographical coincidence that helped cement the relationship, or what McKay describes as “kind of like a flip”: Stewart currently resides in the Flower Valley/Manor Lake area of Rockville where McKay, 20 years Stewart’s senior, grew up. “The very interesting thing is his coming from a Southern background to move to Montgomery County, and me being born and raised in Montgomery County and Rockville moving to a more conservative area of western Maryland,” said McKay, who now resides in the city of Cumberland. “But it’s one of those things where you make the connections that start the friendship.”

If Stewart’s introduction to the opioid issue arose out of recent personal tragedy, McKay’s sponsorship of the Senate companion legislation to Stewart’s bill reflects the societal scourge of opioid abuse in McKay’s District 1 rural constituency at the western edge of the Maryland Panhandle.

McKay’s home county of Allegany – with a population of 68,000, barely more than 6% of that of Montgomery County—is currently shouldering an $800,000 annual bill to provide state-required treatment of opioid use disorder in detention centers. That’s a result of nearly 80% of those arrested and detained for crimes in Allegany County being opioid dependent, McKay noted. “It’s just been devastating to Appalachian Maryland,” he said. Co-sponsoring the legislation in the House with Stewart is another Allegany County Republican, Minority Leader Jason Buckel.

If the initial impact of the opioid epidemic landed hardest in rural areas both in Maryland and across the country, the latest statistics compiled by a couple of state agencies – the Maryland Behavioral Health Administration and Office of the Chief Medical Examiner — bespeak a sharply increasing problem as well in suburban areas such as Montgomery County.

The latest available data, shows 121 “unintentional opioid-related intoxication deaths” in 2021 in Montgo, a 40% increase from 86 two years in earlier in 2019 – and more than double 53 such deaths recorded in 2014. In the first quarter of 2023, there were 34 opioid-related deaths in the county, up from 25 in the same quarter of 2022; the increase was the largest of any county in the state in both quantity and percentage.

In an effort to reduce such statistics, the Stewart-McKay legislation would require that hospital emergency rooms “provide to a patient before discharging the patient appropriate, evidence-based interventions that reduce the risk of subsequent harm and fatality following an opioid-related overdose.”

As Stewart conducted research before drafting the bill, he found that current “best practice” in emergency rooms for complying with such a requirement is to offer patients a remedy with the generic name of buprenorphine, better known by the brand name of Suboxone. That medication, Stewart learned, “not only eases the withdrawal symptoms; it is also what’s called an opioid agonist, which means if you try to take another opioid, your body rejects it and you become very sick, but it’s almost impossible to overdose.”

Despite his long friendship with Haynes, Stewart acknowledged knowing little about the origins of Haynes’ addiction. “He was pretty private about that,” Stewart said, adding, “I do think that physical ailments were part of it. He renovated mobile homes for a living, and it was backbreaking work. As he got into his 30s…it did start to take a toll on his joints and his bones – and I think that was part of how it was introduced.”

After Haynes’ death last year, his family related to Stewart that Haynes had been “going to clinics and seeking rehab” in an effort to rid himself of the addiction. In turn, Stewart believes Haynes’ life could have been saved if he had been offered a medication such as Suboxone when he was admitted to the hospital suffering from a fentanyl overdose.

“His family recounted to me about how…he was given Narcan, which saved his life, but which triggers massive withdrawal symptoms,” Stewart said of the drug designed to reverse an opiod overdose. “He was released in pretty short order, and, because he was experiencing these withdrawal symptoms and feeling awful, he went out and unfortunately purchased more fentanyl, and that’s how he overdosed within eight hours of being released from the hospital. And the second overdose was fatal.”

Stewart contended that “if Brad had been offered [Suboxone] and accepted it, and hopefully he would have, then he wouldn’t have died from the second overdose.”

He continued: “When you have a patient after a first overdose, you have a captive audience – and potentially a receptive audience. They’ve hit rock bottom, and there’s an opportunity there to put them on the track to recovery. But if you only give them Narcan and send them away, it’s a huge missed opportunity, and unfortunately, that’s still what a lot of [emergency room] doctors do.”

To help defray the cost of his proposed new mandate on Maryland hospitals, Stewart’s bill would allocate $500,000 from the state’s Opioid Restitution Fund – derived from Maryland’s share of legal settlements with opioid manufacturers. A total of about $16 million from this fund has been allocated for opioid-related initiatives in the state during the current fiscal year.

In what Stewart called an “eerie” bit of timing, he later discovered that, at almost exactly the same time as Haynes’ death, the Maryland Opioid Restitution Fund’s workgroup had issued recommendations on how the money should be spent. One of the recommendations dovetailed with the legislation he was drafting: training emergency room physicians to utilize prescriptions such as Suboxone, or what are formally termed Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD).

“When I was starting to put this bill together in October or November, the recommendations had just been released,” Stewart said. “And fortunately, this exact bill was one of the recommendations they had for spending this money.”

While acknowledging Maryland is already “leaps and bounds” ahead of Alabama, where Haynes died, on this issue, Stewart said the current voluntary adoption of the MOUD protocol around the state has been uneven in the absence of laws such as he is proposing. “Even if a hospital buys in, that doesn’t mean that every physician in the hospital is required to do this,” Stewart said. He blamed the failure of many physicians to adopt new techniques on “inertia” since they currently “have the autonomy to just do what they’ve been doing for the past 30 or 40 years.”.

As he prepares for the first hearing on the bill, Stewart predicted: “I think part of the pushback we’re going to hear on this bill is that ‘This is the direction in which the hospitals are moving.’ But there are also voices in the medical field that I’ve talked with, who say ‘It’s just too slow. We’re moving in the right direction, but people are dying every day. We’ve got to pick up the pace.’

“So this bill is meant to do that,” Stewart asserted, adding ruefully, “There are going to be a lot more Brads and more best friends that die if we don’t move faster.”

McKay, whose companion legislation will be heard by the Senate Finance Committee in mid-March, expects the bill will be a “heavy lift” in view of the state’s mounting structural deficit.

Although the legislation does not require money from the state’s general fund, “we’re looking to get the funds from the Opioid Restitution Fund, and there are a lot of other bills that people are putting in that would also like to be part of that fund,” McKay noted. But he hopes the fact that the bill “could have a direct [impact] on the saving of people’s lives and better equip our emergency rooms” will give it momentum.

For this reason, Stewart believes the legislation will not attract “outright opposition” from hospitals and other medical facilities that could be affected by its provisions. “I do think they will try to shepherd it into a study,” he predicted. “Fortunately, every single study, every researcher agrees that offering these medications in the emergency [room] is a game changer.

“It will absolutely save lives – there’s no doubt about it. It’s just a matter of political will at this point.”